iOS 14.5 has begun rolling out on April 26th. With its release, all apps must request the users’ permission to track them. It seems the majority of users wouldn’t tap “Allow tracking,” therefore disabling the developer’s access to IDFA, an advertisement ID that was considered essential for effective mobile attribution.

This change has the potential to cause major disruptions to the digital advertising industry. It’s been a bumpy run since WWDC 2020 with numerous things changing along the way, including Apple guidelines and SDK updates on April 27, so let’s gather everything we know

This page consists of five parts to make reading effortless:

- UX changes. What the end user will notice

- IDFA, ATT and what they do

- What Apple suggests instead? Guide on SKAdNetwork

- How did the industry prepare?

- What’s next?

Changes for UX

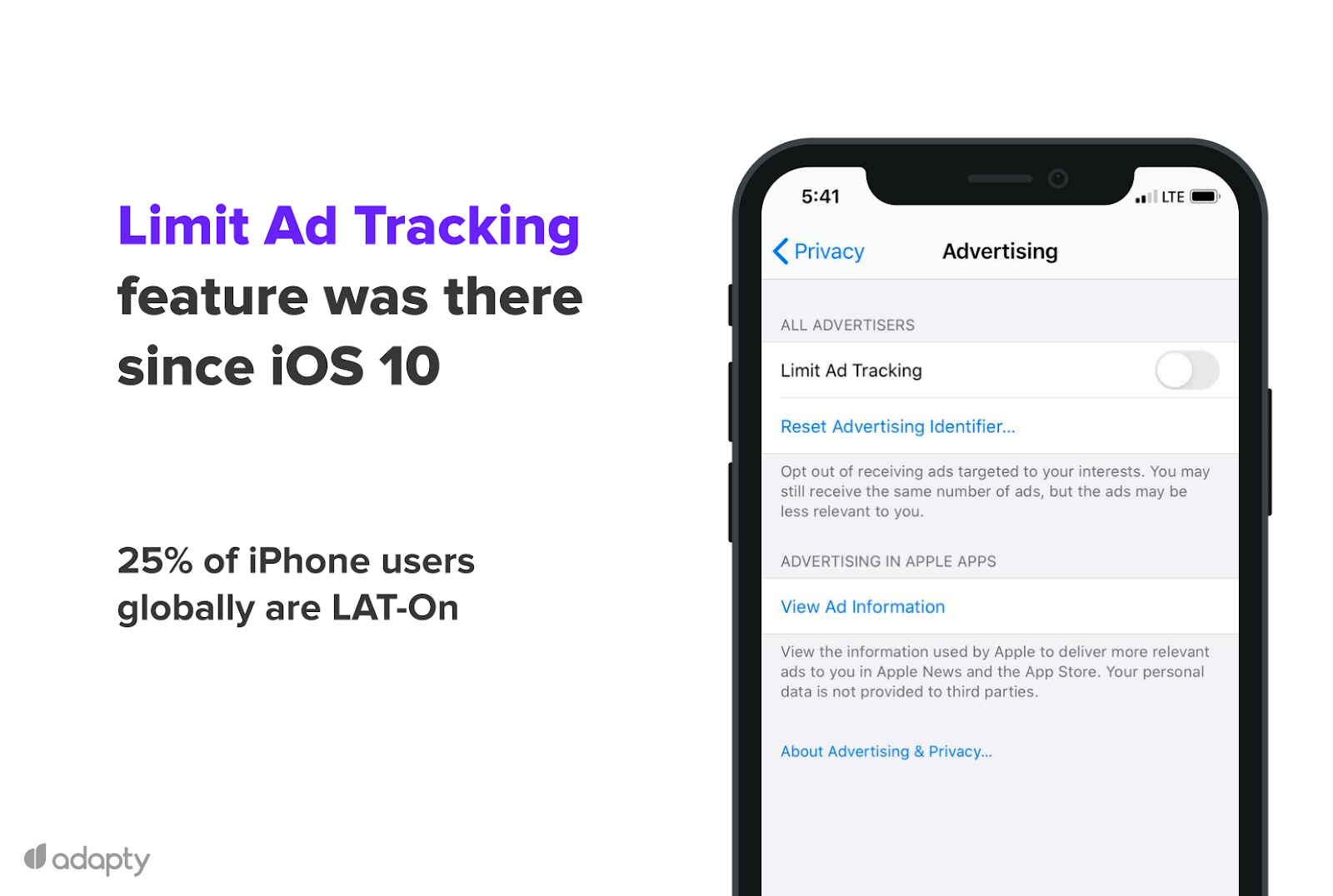

First of all, iPhone users could taste upcoming privacy changes in action as early as four years ago. They just needed to toggle the Limit Ad Tracking (LAT) switch in the privacy settings as the feature was off by default.

A recent survey says that as of 2020, about a quarter of iPhone users made an effort and turned LAT on. The percentage varies across countries, with around 30% in the US & the UK and less than five percent in Brazil and Russia. Numerous developed countries witnessed a steady LAT-on rise after the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018.

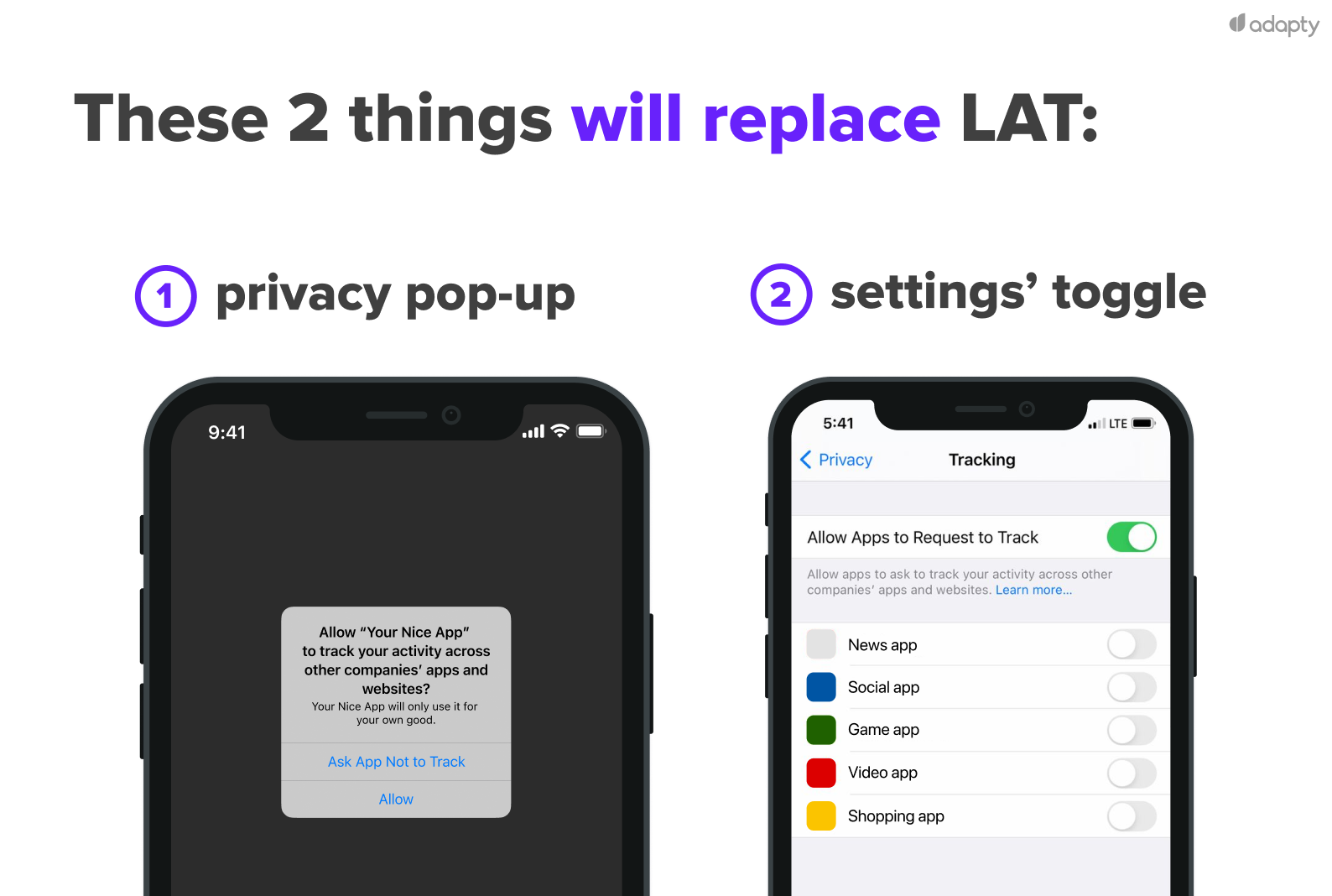

However, this LAT setting toggle will disappear with the next iOS update. It will be replaced by two things: an in-app pop-up and a similar toggle in Tracking settings, alongside toggles for each app.

Let’s say user Michael had LAT turned off. After the iOS 14.5 update, he will receive this pop-up every first time he opens an app.

If Michael wants to stop tracking across all apps and prevent future pop-ups, he will go to Privacy settings and disable “Allow Apps to Request to Track.” Also, he can do just that for particular apps while leaving the general toggle “On.”

In other words: before, Limit Ad Tracking was opt-out for all apps; starting iOS 14.5, it will become opt-in on a per-app basis.

Changes to marketing

Before we dive into shifts, let’s sort the terminology real quick.

IDFA

On the web, advertisers have cookies. This enables advertisers to get notified when a user has taken action like clicking on their ad or installing their app.

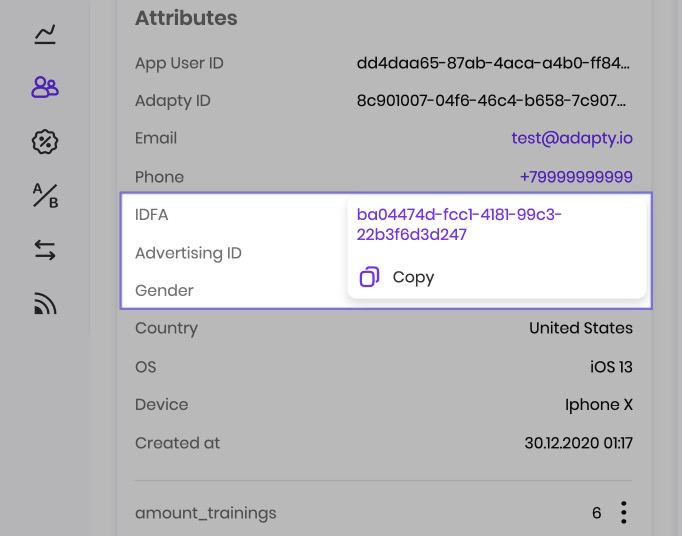

On iPhones, advertisers have IDFA. IDFA is a unique ID that conveys information about a person’s online behavior, app usage, and device features. IDFA does things similar to cookies: it tracks numerous user attributes to optimize ad targeting and reflects whether a specific ad is effective. A bit later, we’ll see exactly what it does.

IDFA was introduced by Apple back in 2012, and Google came up with a similar solution for Android the following year. IDFA usage is a subject of user choice: it can be reset in settings, and it can also be eradicated if the user turns on the Limit Ad Tracking toggle in Settings. In the latter case, IDFA turns into a string of zeros, therefore losing any marketing relevance.

Before iOS 14.5, IDFA was on by default, therefore being an opt-out standard. Let’s just conclude that IDFA is a cornerstone in mobile app advertising.

ATT

AppTrackingTransparency framework (ATT), just like IDFA, is an Apple thing. Introduced at WWDC 2020, this mechanism will manage user consent for ad tracking starting iOS 14.5 update.

Among other things, ATT will handle users’ permission for the usage of their IDFAs. But it’s not just IDFAs: app developers must use the framework if their app “collects data about end-users and shares it with other companies for purposes of tracking across apps and websites.” Alongside ID for advertisers, this includes whether the app uses fingerprinting, email lists for targeting, session IDs, device graph IDs, and other techniques that Apple deems as device-level data.

We can say that ATT is here to weaken the relevance of IDFA.

Remember Limit Ad Tracking toggle from the previous section, replaced by a pop-up and another toggle in iOS 14.5? Well, both of these new things are part of ATT mechanics. We can say that ATT replaces LAT, but in a more intrusive manner.

Once an app has asked for this permission, it will also show up in the Tracking menu, where users can toggle app tracking on and off at any time. They can also enable app tracking across all apps or opt-out of these requests entirely with a single toggle, just like with LAT.

The most important conclusion is the following: apart from LAT and its opt-out approach, ATT requires users to actively opt-in to allow IDFA collection.

Why is the opt-in shift so significant?

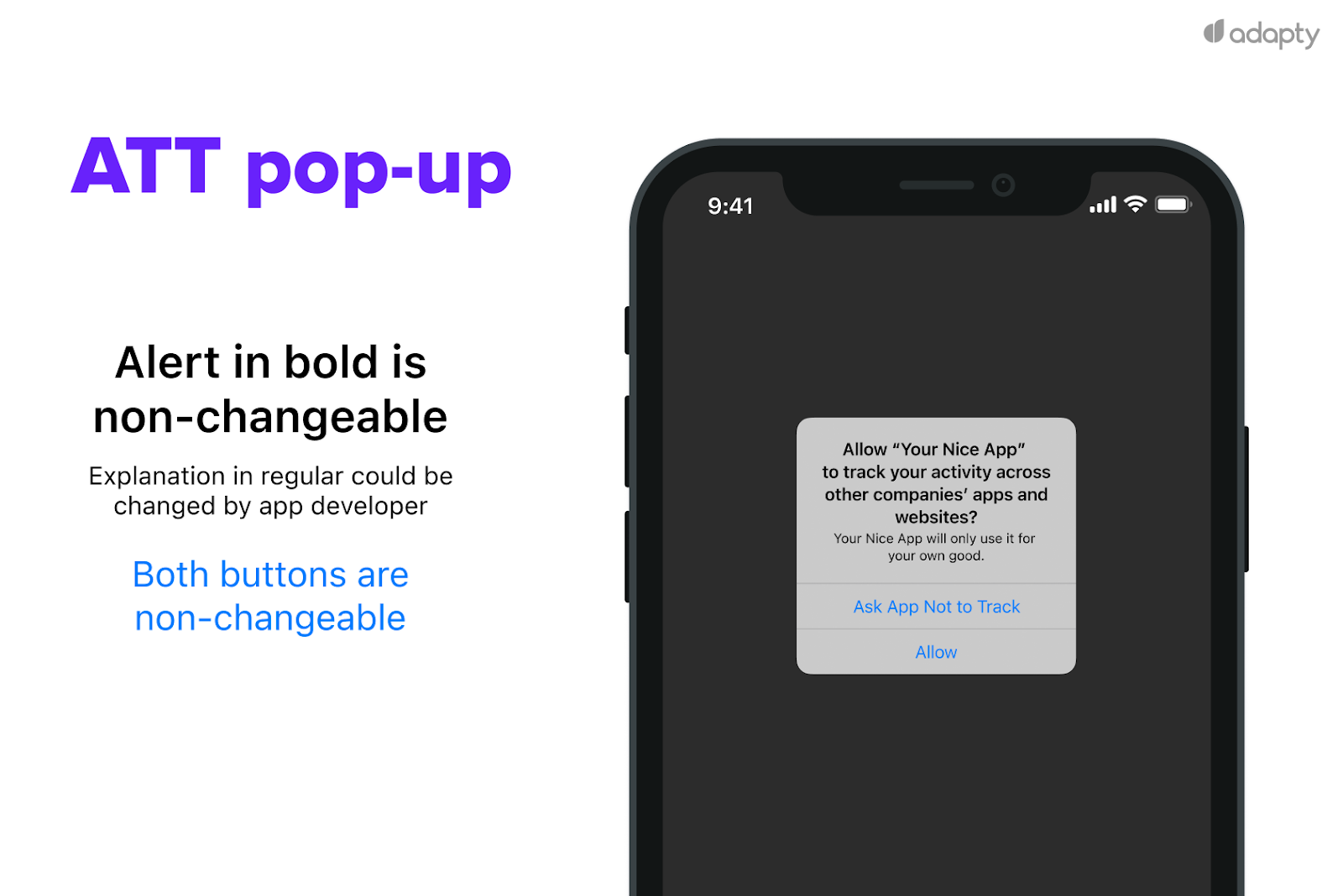

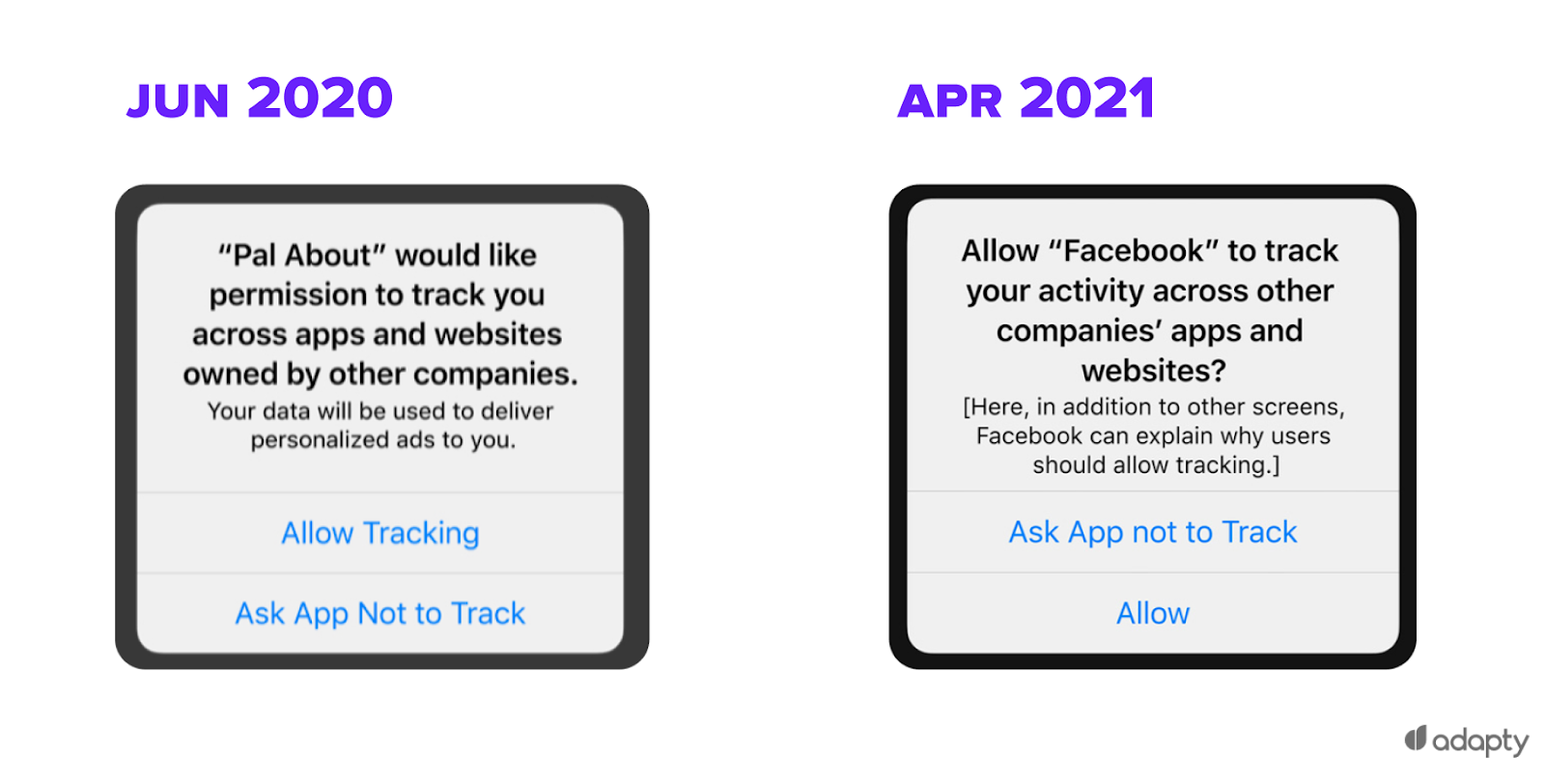

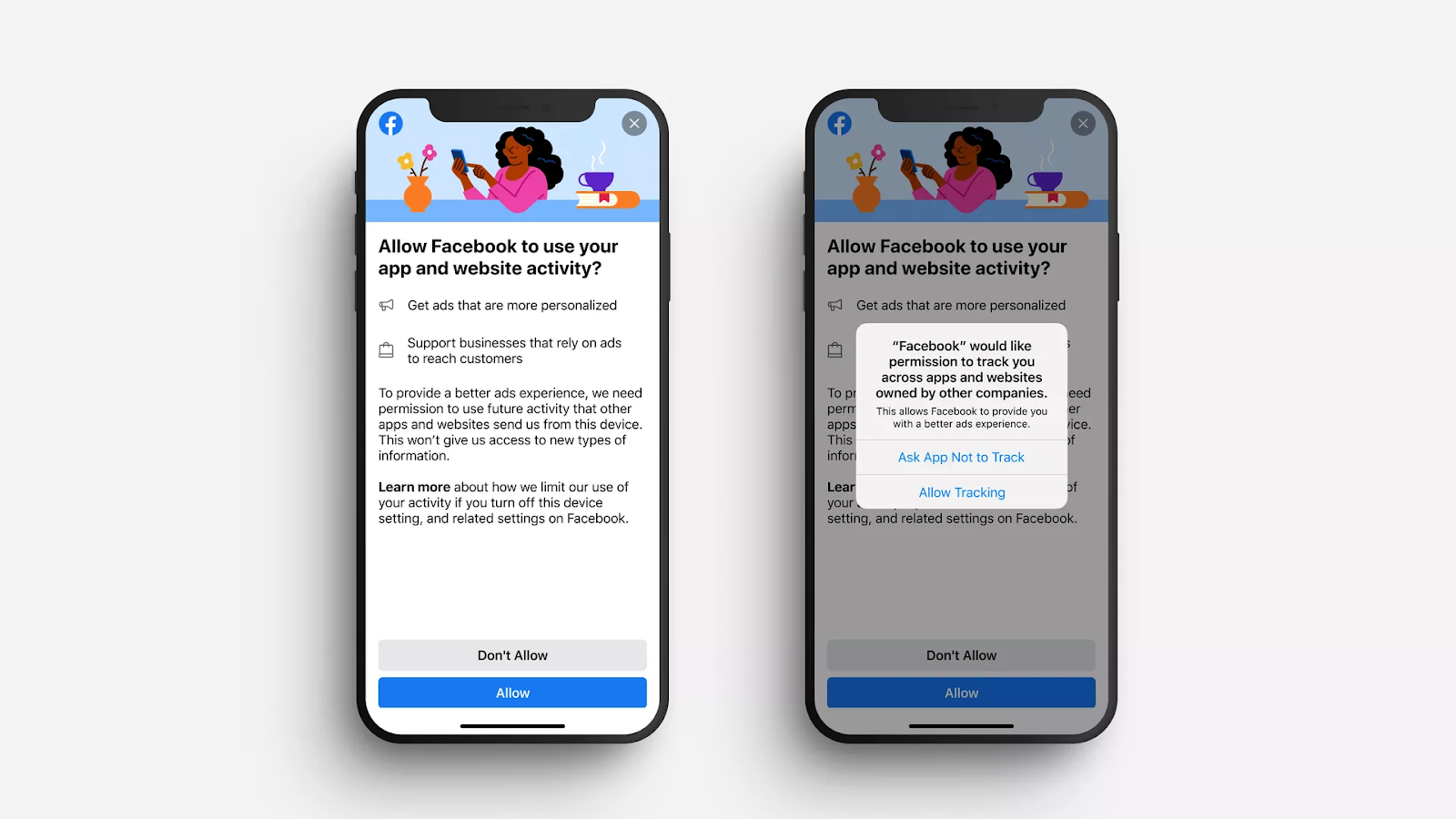

It’s crucial because opt-ins will be presented in the form of an alert pop-up, and advertisers say its tone of voice, provided by Apple, prejudges the user’s decision. See for yourself:

Initial language from WWDC looked even more threatening:

It doesn’t look like most iPhone users will agree to the updated, softened variant, does it?

Well, most experts agree that opt-in rates will plummet. Back in June, analyst Eric Seufert estimated that 80% of users would decide to opt-out. On iOS 13, Apple implemented a similar policy regarding geolocation and asked explicit permission to collect location data; 70% of users chose to opt-out.

Simultaneously, more optimistic analysts cite the example of GDPR on the web, when users acknowledged the value of personalization and allowed tracking, so the opt-out rate this time is predicted around 50%. Also, some experts have been testing the pop-up since mid-March and claim that “the opt-in rates are much better than most of the industry’s estimates.” On April 21, Appsflyer came up with real tested numbers, saying that 39% of users (on a sample of 500+ apps) accepted tracking.

OK, so this shift is crucial because it’s expected to drastically affect the share of users allowing their apps to use IDFA.

What things does IDFA allow developers to do?

First, attribution. Advertisers measure the efficacy of their ads by using the IDFA to tie back a user who clicked on an ad and a user who downloaded an app (made the desired action), allowing themselves to optimize their campaigns better and get a picture of whether they’re effective or not. Here’s an example of how it works:

- An app shows an ad of another app, with a link embedded behind it. Within that link, the URL is a parameter with the IDFA.

- The user clicks on the ad. The click sets off a network request, during which the ad network collects the IDFA before redirecting the user to the App Store.

- After downloading, the ad network SDK collects the IDFA again and matches the two values to perform attribution.

- A brand can then further invest in high-performing channels or redistribute spend based on different campaigns’ performance. It can analyze other attributes of their new leads through IDFA and tune their initial targeting a bit better.

The desired action could also extend far beyond just the install. Besides matching IDFAs, the advertiser sees into events such as clicks, downloads, registrations, and purchases, so they could define some new users as more valuable than others.

So, yeah, IDFA allows developers to measure the effectiveness of their ads

This leads us to the second point, targeting and message personalization. Since IDFA is unique to each device, it can be used to serve highly personalized ads based on user characteristics and activities.

IDFA can also be utilized for retargeting, that is, retargeting ads to lapsed users. For instance, Michael added items to his Amazon cart and left the app. Amazon marketers can create a user segment “Left items in cart” and send Michael’s IDFA to ad networks requesting a retargeting ad about these items to be shown to that specific user segment.

Additionally, there is pacing. Advertisers use frequency capping to limit the number of times a user is shown a particular ad within a time period. They can ask networks to set time parameters to avoid repeated messaging to the same person – identified by IDFA.

IDFA has many roles in the mobile industry. These roles will be mostly broken in iOS 14.5.

Did Apple suggest any alternatives?

Yes, it did. There are two ways a company can behave starting iOS 14.5:

- It can stick to IDFA and attempt to gain user opt-in via the ATT framework. This grants possible access to granular ad attribution data on iOS and all the benefits that come with it

- Get on with aggregate data only, as provided by Apple’s SKAdNetwork.

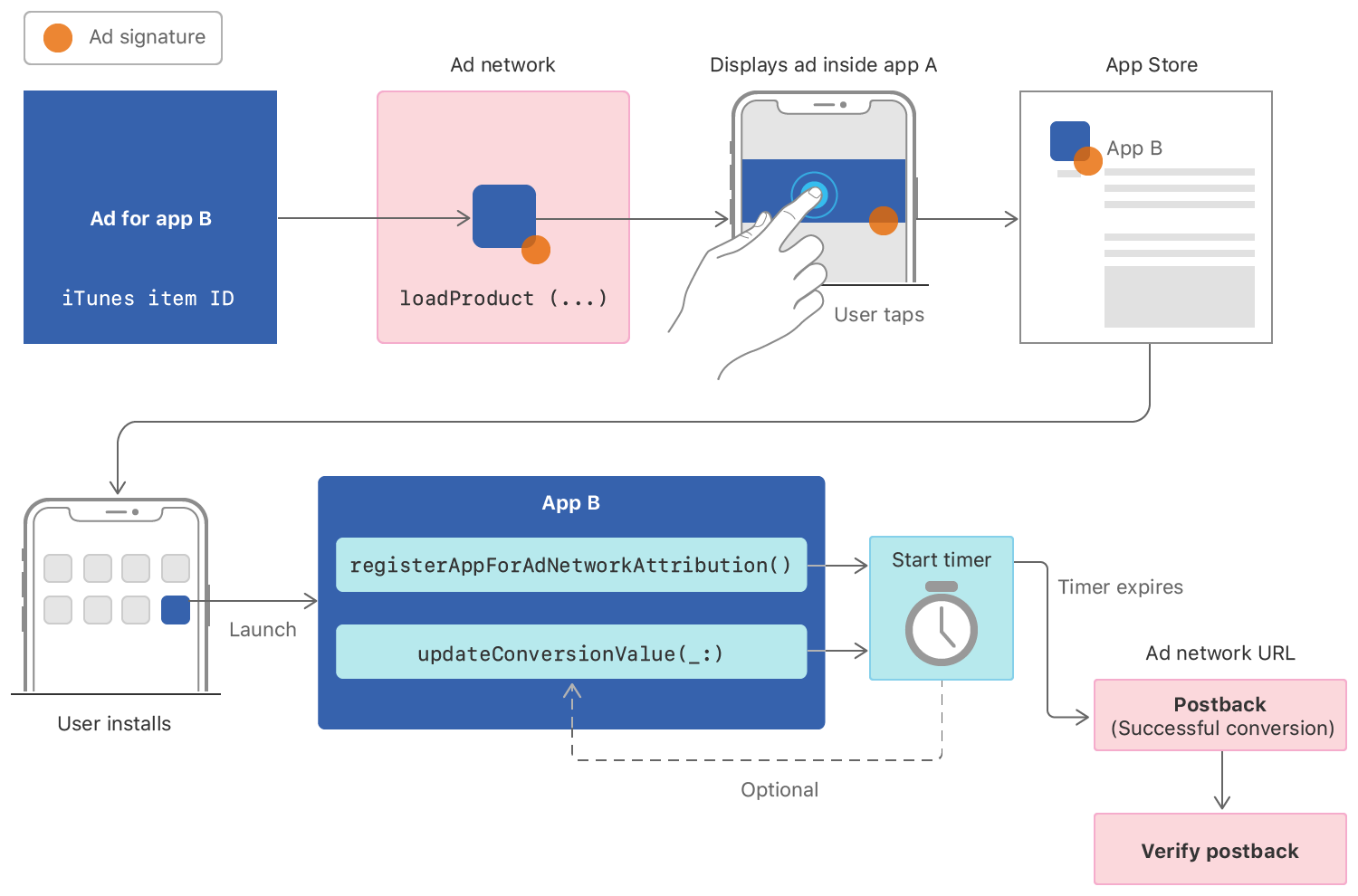

SKAdNetwork is Apple’s new, privacy-focused take on attribution, launched back in 2018. It transmits app attribution data (and a limited amount of in-app event data) at a campaign-centric aggregation level versus the user-centric aggregation level used with the IDFA. Put differently, ad networks will know that a given campaign produced an install, but they won’t know which user generated that install. They will learn close to nothing about subsequent activity in the app after the install.

With SKAdNetwork, Apple controls the initial stages of attribution as it happens on the company’s servers. The data is cleansed of anything that could compromise a person’s identity before being shared with the ad networks.

This comes at a cost. SKAdNetwork proposes a lot of measurement challenges, and many experts claim that it lacks some “critical functionality.” To name a few popular points:

- It’s limited to 100 different tracked campaigns per network. This number simply doesn’t allow for adequate segmentation, as there are often countless sub-campaigns for different geographies, device types, or creatives.

- Campaign identifier as a sole tool for optimizing creatives is basically useless as it doesn’t allow any refined messaging.

- Only one event in conversion management associated with an install attribution isn’t enough. For marketers, measuring campaign performance has historically gone far beyond simply knowing if your app was installed.

- Post-back delay. Postbacks will be generated and sent at least 24 hours after the installation. Real-time optimization won’t be a thing, and networks will be severely impeded in their ability to optimize campaign performance.

There are other problems. Some analysts have suggested ways to improve SKAdNetwork while holding onto a privacy-centric approach.

We’re not sure whether Apple is listening, but it clearly shows commitment to improving SKAdNetwork. On April 27, the company touted its Private Click Measurement technology that helps with web-to-web and app-to-web measurement. It can be used to understand which advertisements drive conversions (such as purchases or signups) with no ATT prompt required.

Apple also announced plans for SKAdNetwork 3.0, coming live with iOS 14.6. Apple will allow devices to send postbacks to multiple ad networks. The winning ad network will receive an install validation postback for the successful ad impression, while up to five other ad networks will be alerted that they didn’t win the attribution.

In general, SKAdNetwork isn’t viewed as a sufficient substitute for the tools industry loses with ATT, with some key features, such as reengagement campaigns and web-to-app measurement tools, still absent.

How does the industry prepare?

First, developers checked if marketing tools besides IDFA fall under Apple’s definition of not-so-private. For instance, initially many suggested that fingerprinting, a method involving tracking internal characteristics of users’ devices, will remain available. It didn’t: ATT prompt should be used if the app wants to use this mechanic.

Email lists were also included in the examples of tracking under the jurisdiction of ATT. Apple claimed that developers must gain consent through the pop-up to use custom email addresses for retargeting and look-alike audiences, therefore removing one of the last ways to keep iOS targeting effective after the IDFA ditch.

We’ve extensively covered Apple’s arguments on putting these mechanics into the ‘tracking” list, as well as if Apple left any workarounds (no, it didn’t).

Some also assumed that Facebook silently suggested a replacement for IDFA in the form of FacebookAnonymousID. That turned out not to be the case; we’ve tested it and explained why.

Still, some things will continue to work. Deep linking, including deferred deep linking, falls outside the scope of the updated anti-tracking policy. Of course, Android is not affected in any way as well – for the time being, at least.

When it became clear that Apple is putting all mechanics that might derive data from a device for the purpose of uniquely identifying it under ATT compliance, many developers started thinking about how to maximize the ATT opt-ins.

The initial idea is to customize the pop-up alert field to convince the users to accept tracking. Still, this string per se seems to have a relatively small impact, compared to the formula Apple puts into the alert itself.

This is where ‘soft prompts’ became popular. The idea of the soft prompt was to gauge a user’s choice before officially prompting them for the moment that really counted. Facebook, one of the fiercest opponents of Apple’s ATT changes, has become one of the first major companies to come up with a dedicated screen that gives “additional context” before the iOS alert rises and will encourage users to allow tracking.

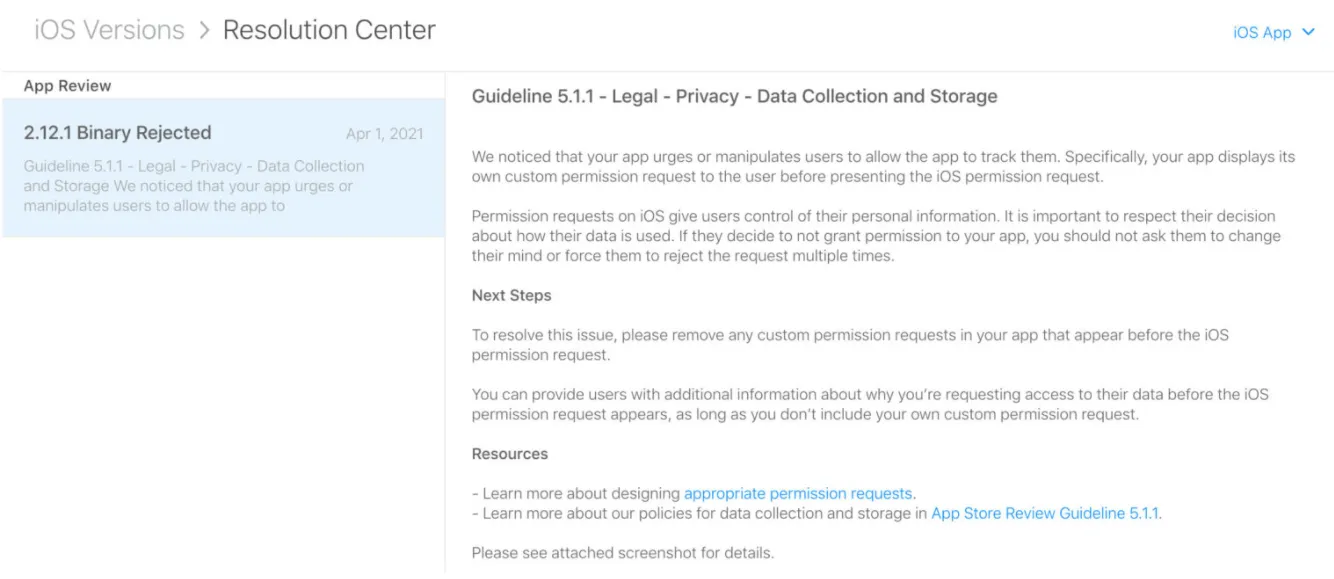

However, in April, we found that Apple considers such prompts manipulating and won’t allow them, as we have seen from this App Store rejection report:

Simultaneously, Apple clarified that “you can provide users with additional information about why you’re requesting access to their data before the iOS permission request appears, as long as you don’t include your own custom permission request.” So you can make a preliminary screen explaining why your app needs tracking. Just don’t insert a custom prompt of your own.

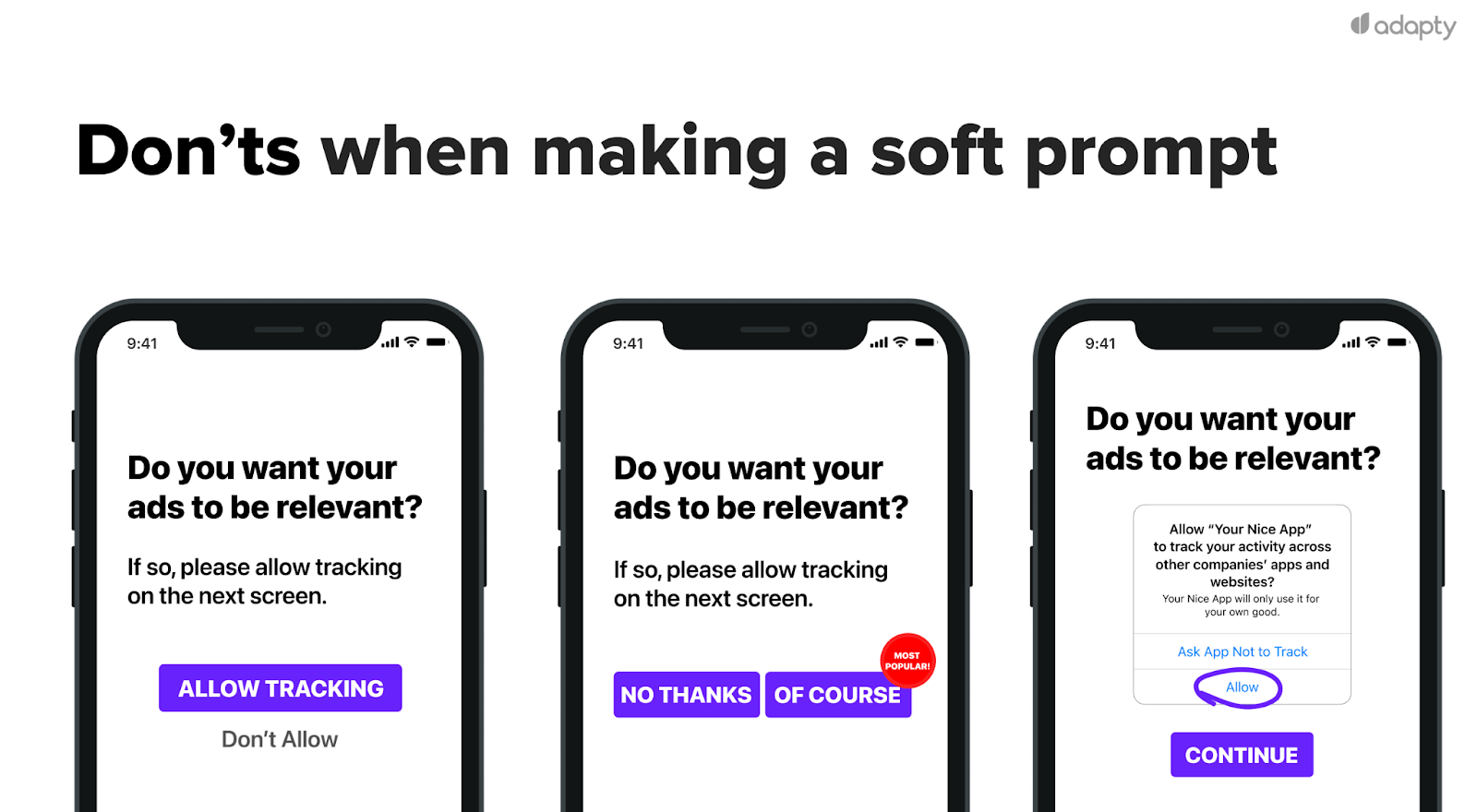

Here are some examples of what you shouldn’t do when designing a pre-prompt.

In the first case, the buttons mirror the functionality of the system alert. In its Human Interface Guidelines Apple claims that you shouldn’t create a button title that uses “Allow” or similar terms, because people don’t allow anything on the pre-alert screen.

In the second example, the red bubble represents a visual technique that might subconsciously influence the action taken by the end user. Apple maintains that pre-prompts should serve only to educate the end user about their decision, and won’t allow this app during the review.

Lastly, you shouldn’t show an image of the standard alert or modify it in any way. It’s written in the same Guidelines. You also should promise a digital good reward for clicking “Allow”, but we didn’t include that in the image since it’s kinda obvious. That’s it.

While testing ATT, some vendors used dark patterns in order to encourage users to accept tracking. An app was rejected from the App Store after triggering the ATT pop-up immediately afterward the user agreed to the main consent GDPR pop-up. In this case, Apple believed that such alert positioning is a case of user manipulation.

What’s next for mobile marketing?

With the weakening of IDFA and other tracking techniques, Apple made other instruments’ weight larger. Now the App Store Optimization will become more relevant, and Apple could utilize its own advertisement platform.

Apple already sells search ads for its App Store that allow developers to pay for the top results. In searches for “Twitter,” for example, the first result is currently TikTok. Financial Times recently reported that the company plans to add a second advertising slot to its App Store search page’s “suggested” apps section. It will allow advertisers to promote their apps across the whole network rather than in response to specific searches.

Some companies say that they will pay more attention to detailed ad creative performance metrics on Android campaigns, then pivot those learnings over to iOS.

Others may focus on using existing Customer Relationship Management means such as push notifications, email, and other social channels, including ones outside the app, to engage existing users in maximizing retention and revenue.

Companies that operate several apps can continue to use identifiers for vendors (IDFV) in order to track users and cross-promote apps. IDFV still remains a highly accurate, device-level instrument.

How Adapty fits in?

Some instruments lose their relevance, and some gain. With the dust settled, we can say that paywall A/B testing definitely belongs among the latter, representing one of the major ways to increase your revenue.

We see that with Adapty A/B tests, companies are increasing their revenues by 40% within a few months. After the integration, setting up paywalls and A/B tests does not require any coding and can be done directly by marketers. They can compare paywalls, change price tags, manage payment screens without app releases, and effortlessly analyze your business’s health.

With the 14-day trial and five strings of code to get you going, Adapty is worth checking out.