Over $1M MRR, millions of users, tons of insides

Updated: February 15, 2023

Listen to the episode

The second episode of our SubHub podcast, in which we invite top guests and discuss with them the business of mobile apps: subscriptions and monetization, hypothesis testing, product fit, and more.

In the second episode, our guest is Mikhail Prytkov, co-founder of Simple, an app about interval fasting and proper eating habits. Simple has repeatedly been at the top of the AppStore. Mikhail told:

- About their approach to research and why experiments become less effective over time;

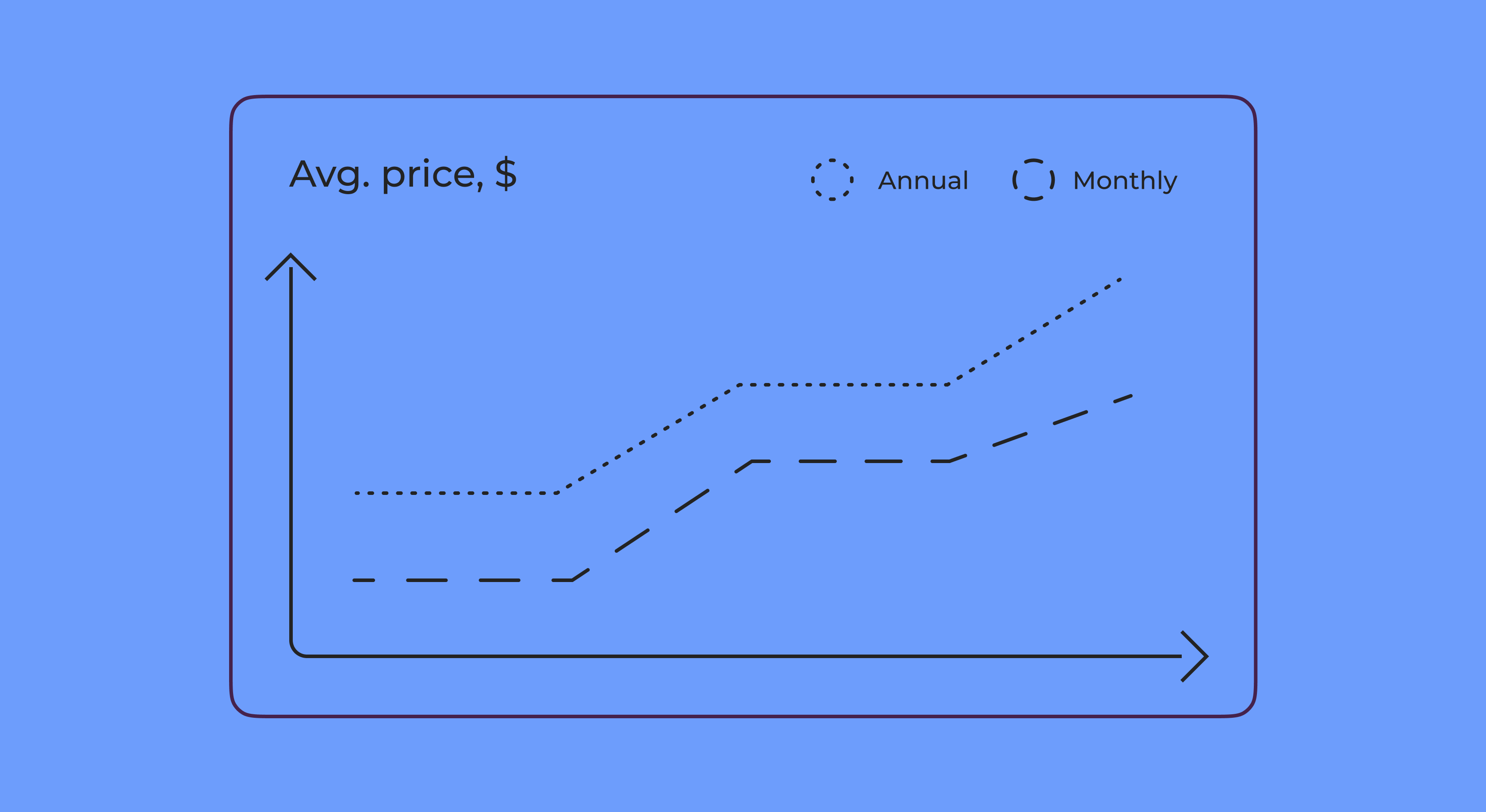

- About the factors to consider when choosing a subscription period;

- About web subscriptions: their features, benefits and opportunities;

- and, of course, the top of the AppStore and how you get there.

The episode is already available on all popular platforms (in Russian).

The full transcript is available below, translated with deepl.com

Introduction

Vitaly Davydov: Hi everyone, I’m Vitaly Davydov.

Nikita Maidanov: And I’m Nikita Maidanov.

Vitaly Davydov: We do a podcast about SubHub mobile subscriptions. We talk about everything related to mobile subscriptions, monetization, and we invite prominent guests to join us to listen to their stories of mobile app growth. The podcast is created with the support of Adapty. We make this service for analytics and growth of mobile apps with subscriptions. With Adapty, developers completely close the technical issue of connecting subscriptions in hours instead of months, and marketers increase revenue from subscriptions by an average of 25% with A/B tests and Paywall.

Nikita Maidanov: And we’re already starting our second episode. Our podcast has lived up to its second episode, which not everyone does. We have our second guest, Mikhail Prytkov, founder of CEO Simple. Hi!

Mikhail Prytkov: Hello!

Vitaly Davydov: Hi, Misha.

Mikhail Prytkov: Hello!

Vitaly Davydov: Thank you for the invitation.

Nikita Maidanov: Thank you for coming.

Vitaly Davydov: Misha, tell us how your journey began.

The path from a paper to Simple.

Mikhail Prytkov: It was a long way if we step back, look how it all developed for me. Generally speaking, I started some of my first contacts with marketing from the marketplace back in the days before Avito. The first thing I did was transfer ads from the paper Iz Ruk v Ruk newspaper to the site. That was a long time ago.

Vitaly Davydov: With your hands?

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes, by hand. By the hundreds a day. It was a very long time ago. It was my first IT experience. It was back in my student years. Then there was a computer hardware store, where I was already engaged in real marketing, buying traffic from Yandex.Direct, from MarketGid, from these stories. After that, I thought I should try to figure it out, work in my specialty. By training, I was supposed to be implementing SAP systems, these big infrastructure things in big factories, and so on.

I came in, it took me about three months. I realized that the cycle of selling and implementing such systems was years. After coming into contact with marketing, when everything happened in days or hours, I can no longer even perceive such long cycles.

Fotostrana

Mikhail Prytkov: After that I realized that I needed to look for something closer to marketing, something more understandable in a large company. I was lucky enough to come to a company called Fotostrana, which is part of Embria. I worked there for about three years, as I recall. It was a very interesting experience. I actually realized a lot about marketing there. I understood how in principle it can work, how it works at scale. I think we were the biggest and the first there. My first accomplishment was very simple. I wrote to everyone I could find who was developing the app for VK and OK. We were probably one of the biggest buyers of in-app advertising at the time.

Vitaly Davydov: Tell me in a nutshell what Fotostrana is. Perhaps not all listeners know.

Mikhail Prytkov: “Fotostrana” is a social network. I haven’t touched it for a long time. They have evolved a lot in recent years. But at the time it was a social network that combined “Dating,” various apps inside. There were apps about virtual pets, mini-games of various kinds. From the marketing point of view, you could use both the dating theme, which was somehow similar to what Badoo was doing, and the games theme, and it all worked great for different audiences, got along quite well with each other too, which is amazing.

I was there to engage both audiences. Correspondingly, from different apps, from Facebook, from OK. Then targeting advertising began to appear in Russia. MyTarget appeared with My World. We bought a lot of adverts for “Photostrana” there. We were probably one of the first buyers in principle. Many of the rules that ended up in myTarget were written based on how Fotostrana interacted at the time…

Vitaly Davydov: So you were pumping your audience from one social network to another.

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes.

Vitaly Davydov: It was the beginning of that performance marketing, as you started doing it.

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes, that’s right. It was a very interesting experience. Then the company grew very quickly in terms of revenue and number of people. At some point I realized that for me the same experience began to repeat itself. I wanted to find something else interesting.

Then Embria offered to participate in the DataLead project. DataLead had already been in existence for a number of months at that point. The idea was to build on Google Bidder, which could algorithmically redeem advertising.

Vitaly Davydov: Let’s elaborate on that a little bit more. You mean Embria as a fund or as a company?

Mikhail Prytkov: As a fund.

Vitaliy Davydov: As a foundation. They had the DataLead project. And you were invited there as a partner to take part in building that product.

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes.

Vitaly Davydov: Tell us in a little more simple terms what exactly DataLead did.

DataLead and the agency business

Mikhail Prytkov: The main idea was that we could improve traffic buying with the help of technology. We will be able to better select the users we need to redeem for the advertisers’ tasks, we will be able to assign more correct bids. With technology, this can all be successfully scaled. But as happens in startups, the reality turned out to be a little different. We didn’t manage to start making money specifically with technology at the very beginning. So we thought, “OK. Let’s try doing media buying. If we turn this into an agency, let’s see how that works.” We tried with a lot of hard work for probably half a year to find things that we would be good at, those bundles of advertisers that are effective for us, those bundles of channels that are effective for us in terms of marketing, and we turned to a model where we would be for foreign companies-at that time we were working almost entirely with foreign companies-that would be guides to the Russian market, and also help them buy traffic in Facebook.

Vitaliy Davydov: Let me clarify what year it was. When we talk about buying traffic, is it mobile or web?

Mikhail Prytkov: It was almost entirely a mobile story. Even back then. I think it was about five years ago. Maybe a little more.

Vitaly Davydov: That is 2015-2016.

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes. We saw a big prospect in the fact that many companies… mobile advertising was just emerging back then in terms of the fact that few companies knew how to work with it effectively. And we had already got our hands on it to a certain extent. So it was quite easy for us to get new clients and negotiate with them, and we got very good results.

Vitaly Davydov: Let’s get a little more specific here. When we talk about mobile advertising and mobile app buying, do we mean Web to App? Or do we rather mean monetization through which things? Just catching up on traffic and marketplace or through subscriptions or in-app advertising. Specify who exactly were you working with?

Mikhail Prytkov: The clients were absolutely diverse. 80-90% of the clients were various mobile applications. Dating, games, utilities. A lot of different ones. Accordingly, we only bought for mobile apps, without the web. It’s all an absolutely classic model. I think if you look at the trends, you can see that every year it became more and more difficult for the agency, because the level of education of the clients increased. They were able to buy more effectively. Facebook, Google and other platforms started providing more effective tools to optimize their purchases.

Vitaly Davydov: For example.

Mikhail Prytkov: Optimization for conversions, for the valuation. Accordingly, applications could buy only those users who are most likely to be effective for them. The number of media-buyers, those who could make a purchase by hand, their number was growing, they were transferred to the internal departments of the company, and the level of preparation of the clients was increasing accordingly. For the agency, of course, this reduced margins. So at some point we realized that we needed to move on, to make a technical platform that could distinguish us from the market. We wouldn’t just be an agency, but we would have a tool that would still increase the efficiency of procurement on our part. We did such an interesting story. We invited a very large number of outside media people, not working for us various designers, to draw creatives for our advertisers.

The advertisers could run traffic to these creatives, and accordingly, they would have a greater variety of creatives. Accordingly, there is a higher chance that one of them will work and bring a good result.

Vitaly Davydov: It was something like a marketplace. Roughly speaking, as a developer of some kind of app, I came onto your platform, and I had a large library of tentative freelancers or people who could draw creative ideas for me. I could talk to them, negotiate with them, do something else, and I would run ads right through you and see what happens.

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes.

Vitaly Davydov: It sounds cool.

Mikhail Prytkov: Yeah. It all worked pretty well. But all the same, the pressure of the market, the pressure that the education of the customers was growing, it forced us to go into making some products by ourselves. I mean mobile applications, for example. So it was clear that part of the revenue that could stay in the agency, the agency’s profit, it would be constantly shrinking. If you don’t do something that supplies you with long-term revenue, and then all the apps with subscriptions started to appear, there was a boom of cross-fitness apps at that time, they were earning very well, they were quickly rising in the tops, it was obvious that if you didn’t start doing something yourself, it would be very difficult to stay afloat as an agency. At that point, my partner and I decided to get out of the business and start something new.

Vitaly Davydov: This is approximately what year, so that we with the timeline oriented?

Mikhail Prytkov: It was about three years ago, about 2018.

Vitaly Davydov: It turns out that 2018 was the heyday of fitness apps.

Mikhail Prytkov: Even slightly earlier, 2017 was. 2016-2017 was already feeling good for fitness apps. But you could see from the trends where it was all going. It is absolutely obvious that if you do not start doing something of your own, it is extremely difficult to stay in this market. And basically, based on the current situation with agencies that I’m seeing, a lot of people have started making their own apps. Either publishing other people’s apps or making their own. But one way or another, they were looking to expand their business model. They are quite successful that way.

Vitaly Davydov: It is amazing that now almost any agency that was just helping to buy traffic five years ago, almost everyone has got publishers. There are actually more and more of them every week. I’m even surprised.

Mikhail Prytkov: That’s right. Because on the real market, the ability to do quality performance marketing is an extremely important component of an effective business. So having that understanding, having an understanding of the numbers that are out there, having an understanding of how the economy works in this case, they naturally have a desire to do something on their own.

Simple

Nikita Maidanov: That’s how Simple appeared, right?

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes, that’s roughly how Simple appeared.

Nikita Maidanov: Was it the first idea about fasting, or did you go through a lot of ideas before settling on it?

Mikhail Prytkov: We approached it this way. In fact, after leaving Appness, me and my partner began to think about health, because the age is already 30. When you’re 20, nothing bothers you, and when you’re 30, you begin to understand that you can eat this and you will feel so, and this is better not. And here you better get more sleep. These kinds of thoughts start to occur.

I lost eight or ten pounds at that point. I decided that this was an interesting topic. When we began to understand, dig deeper, it became clear that the market is enormous, nutrition and weight loss in particular. It’s very segmented. There’s a lot of different things. There are a lot of different diets, a lot of different approaches. Diets come and go. But there are certain fundamental things that remain as they were, nothing happens to them.

Fasting is the main one, because from an evolutionary point of view, it is customary for people at certain times not to eat because of a lack of food. From the point of view of religion, this is a very understandable topic for everyone, expressed through the various fasts that exist in almost all religions. And at the same time, a trend began, primarily in the United States, among the celebrities on the topic of how they effectively control their weight by fasting. Accordingly, we chose this topic; we discussed it for a long time with Yuri Gursky. We knew him for several years, we communicated and crossed paths one way or another, and the idea arose to make a joint company on how to change people’s eating habits, based on the methodology of interval fasting.

2024 subscription benchmarks and insights

Get your free copy of our latest subscription report to stay ahead in 2024.

How did it work out to successfully grow Simple

We started the company about 2.5 years ago. We spent some time on development, to understand what kind of product users needed. After that we started to grow fast enough. That is, understanding how paid channels of attraction work, understanding how we can build monetization, how we can build a product that would really help users. We put it all together, and we had pretty good growth. We are still growing. We are holding on to our position quite well; not only on iOS, but also on Android and the Web. A lot of different things have already appeared.

Vitaliy Davydov: Going back one step. You actually did a deep re-survey. You looked at what is real in health… I mean, first, it all started with some personal problems, with the desire to improve your health. You started digging into that topic. You started looking into diets, starvation and so on. You really had to deal with this subject and this coincided very well with the moment of time when this subject became global.

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes.

Vitaly Davydov: It’s quite unusual that it appears like this. After a deep reserch. It’s interesting.

Mikhail Prytkov: At that time there were already a couple of such notable applications. You could see that they were growing. One app was even without monetization, but it was clear that from the point of view of user experience it was done quite well, it was growing fast, people really got results, that’s the most important thing. So there was clearly something there to do. You have to understand that the market is really huge. People are very aware when it comes to being overweight, when it comes to their health. They really want to keep an eye on it, they want to make sure they don’t get more problems. They want to feel better, more energetic, more active, not get sick, and so on.

So the willingness to pay, the willingness in general to use the product, to pay for it, it is quite high. This is basically all you can understand from the research, even without launching the product. Despite this, we did a lot of live research, surveys, tests, screenshots, when there was no product yet. We launched a separate product, a separate app, on which we tested the marketing before we launched the main app. That is, we used different mechanics to make sure that the product was really needed, that it would really meet the need of the users.

Research to run Simple: an additional application and hypothesis testing on it

Vitaly Davydov: How did you measure this? It turns out that before you launched the main Simple, you made some kind of Simple Light. That is some version under a different name. You started to spill traffic on it, obviously, to measure something. What should we be looking at?

Mikhail Prytkov: We looked at the entire conversion funnel. It is clear that in such a light product you cannot make a full-fledged user experience, so long that the cycle works very well. But you can understand the basic funnel, how much users understand what you broadcast in your marketing materials, how much they understand what is written on the Store page, how onboarding is going, what’s inside the application. They basically understand it or not. Whether there are problems at any steps. How willing they are to pay, how they cancel. These are the kinds of things you can use in this kind of approach.

Nikita Maidanov: Why a separate app, why couldn’t you just run it on Simple, even if it was unfinished at the time? All the onboarding, all the flow startup was ready, since you launched another app with it. Why couldn’t you launch it on the main one?

Mikhail Prytkov: Very simple. This was done in order to parallel the work. In fact, one team was doing the experimental application, and the main team was doing the main application. If we had done it all within the framework of the basic version of Simple, we would have just lost time preparing the experiment. And this way we were able to parallelize and save time.

Nikita Maidanov: So in fact we tested twice as many hypotheses as we could have.

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes.

The launch of Simple.

Nikita Maidanov: How do such projects get off the ground? You told me everything so wonderfully. They gathered and decided to do all this.

And then it began to grow. For listeners who may also want to launch their own project, did you attract investment, assemble a team, how did this process work?

Mikhail Prytkov: This is roughly how it happened. We raised the money and used the money to find developers. We tested hypotheses in terms of what we should do. We gathered a team and began development, and we are still going on.

Vitaly Davydov: Who was responsible for what from the very beginning? You two started together, didn’t you?

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes.

Vitaly Davydov: Who was in charge of the product? Two key components. Procurement. I understand that you handled it. Procurement, marketing, optimization-anything to do with money. But you’ve got to have somebody to do it, to make it fun. People would stick around, use it, and so on.

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes, I was involved in the whole marketing, buying, onboarding, and so on, monetization part. On the whole, the business part. My partner dealt with the product, the development, the content, these components.

Experiments

Nikita Maidanov: You talked about an experiment. You raised the money, you launched the experiment. How do you know when you’ve had enough of experiments and can launch them? What should we look at here? When enough is enough, how much should be spent on experiments?

Vitaly Davydov: Another good question is where to get benchmarks. You make an application, you see some figure. 10% conversion rate. Is that okay, is that enough for us? How can you be sure that when you move from that app to the main one, you won’t have numbers that are 2-3 times different?

Mikhail Prytkov: This is a good question, because we encountered exactly the same thing. It seems to me that people in general underestimate the amount of experimentation that needs to be done to be sure of something, to be sure of their metrics. In terms of starting out, you have to talk to everybody you can talk to about this topic, who’s doing something similar, to get at least a rough idea of what’s happening in the marketplace. It’s very hard to compare apps that don’t sell the same thing. So conventionally, if you’re comparing a weight loss nutrition app to another weight loss nutrition app, you can somehow imagine the metrics.

It’s going to be roughly similar. But if you’re comparing a photo editor to a weight loss, they will be two completely different universes with their own laws, metrics, and user behavior. They’re completely incomparable things. There are different reports, there’s different data that you can take from AppAnnie, Sensor Tower and similar systems. There are different reports that they put out. AppsFlyer report. It’s a research question. We need to communicate as much as possible.

The second issue is understanding your data, understanding how competitive you are in general, in principle. That can be tested in different ways, because a company has some ambition. It can, within that ambition, figure out if it can fundamentally meet it. To grow quickly, you actually need several things. In addition to available resources in terms of money, you have to have a good LTV, which can be expressed in different ways, but now to simplify, just a good LTV and an understanding of how to attract users. If we’re talking about paid channels, for example, there’s still the market and competition that interferes with that.

So conventionally, you don’t know if your LTV is good until you go out and buy traffic and find out if it really is. For example, if you take Facebook, Facebook has an auction that reflects the reality of the market. The higher your LTV, the more efficient you are at buying, the more users you can get from the auction. But the volume is completely non-linear. That is, conventionally, at an LTV of $10, you can take a thousand installations, at an LTV of $12 – 5,000 installations. But to make an LTV of ten dollars to twelve dollars, you have to work hard. Within this ecosystem, you’re trying to find a way to exist effectively. In order to do it really effectively, you have to work on each part completely separately, because even the same LTV, especially in the subscription business, is a combination of quite a few different factors. Starting with just the cost, the duration of the subscription, the cofactor, to what extent you can attract organic traffic using your attracted paid traffic, and so on.

You have to take apart each metric into smaller metrics and optimize it. So it’s a very big time-consuming job. If you simplify it, in many ways, how well you build a product, in principle, how fast it grows depends on the number of experiments you can run.

Vitaly Davydov: What do you mean by experiments? Give me an example of some experiments.

Mikhail Prytkov: Starting with the basics, let’s say, the price is not 30 dollars, but 50 if we’re talking about a subscription, and ending with more complicated mechanics, like how do I invite my friends to the product, why would they be interested in it, how to close this cycle, so that people invite others and they invite again and so on.

Vitaly Davydov: How does it work? Let’s say you invent a new feature. We need to make users invite other users. You run one experiment, the second, the third, the fifth. It doesn’t work. When do you have to stop?

Mikhail Prytkov: It’s important to understand that the data come from different directions. It’s not just the experiment itself, but also various studies. That is, we conduct a lot of reserches, both qualitative and quantitative. We just ask users what they think about this topic, whether you like it or not. Do you understand it or not. Are you willing to pay for it or not. Are you willing to pay that price or not. How men and women behave in this situation. What other sub-segments are there where we have to articulate what we’re selling differently, and so on. This gives us an understanding of whether this experiment is important, whether it will work for the whole audience or rather not. How do we structure it in the right way to make it work for us. By collecting data from different sites, we can much better prepare and formulate the experiment itself, and understand when it’s worth stopping.

Vitaly Davydov: How do you do this? Do you write to users in the mail, or do you offer to do it through in-app mechanics, how does it look in practice?

Mikhail Prytkov: It may be different. Sometimes we just invite users from within the app. We have a Facebook group. We sometimes recruit users there. There are also specialized services, for example, user testing, where you can collect users and make different surveys. There are services for carrying out surveys. SurveyMonkey, for example. Quite a few. All of them are used for different tasks. So we analyze some things this way.

There are various methodologies on this topic. This is all known practice. This is easily found on Google, all the information on this topic. It’s actually very important, because it gives a huge amount of information which is not obvious at first glance. Everybody gets used to their products, they already see them every day. How this is perceived for the first time by a 30 year old US user, a housewife with two children, it’s completely incomprehensible.

Vitaly Davydov: Can you call them directly?

Mikhail Prytkov: We have three UX reservers who do this in-house.

Experiment for Subscription Prices

Nikita Maidanov: For example, you want to test $30 or $50, as you said on peyvole, for example. You run an A/B test on Paywall with different subscription options and enter traffic. How much money does it take to test one such hypothesis?

Mikhail Prytkov: There are different experiments. Depending on the stage of the funnel, they require different investments in themselves. Experiments with different prices are among the most expensive in the time it takes to understand all the fluctuations. In addition to getting some result, you have to match it with seasonality, for example, intra-weekly. It’s different, there are different users coming in. If you have a trial, what’s the conversion from trial to subscription at different prices. If you have an annual subscription, what’s the user cancellation curve going to be, what’s your prognosis for renewing the second year. In fact, it takes a few weeks in a good way to check the price. And on decent amounts of traffic. Then you understand the fluctuations, then you understand how it works within segments and how it affects LTV real, given all the subscription renewals and so on.

It all takes time. It actually costs a lot of money. I think experiments can well cost tens, and in large companies, hundreds of thousands of dollars. This is all usually built into the models. Usually everyone understands that there’s a risk of losing n money on such an experiment. We go for it because there is such a chance of getting a revision. That’s why it’s all calculated; it’s all mathematics. There are all the models and formulas. You just have to work with it. Usually the experiments around money, around the billing itself, give the biggest return, in terms of LTV, because people perceive… the easiest way to treat experiments with money is to look at how users behave in real life, how they evaluate this or that product or service, what the cycle of using that service is. For example, if it’s a question of how long a subscription should be, it depends very much on what people’s cycle of use is in reality.

Vitaly Davydov: Can you explain here? What is the cycle of use in reality. Suppose there is some prila that is used almost every day. Maybe meditation. It involves almost daily use. Or something like that. How do you figure out how many subscriptions you have to put in there, how long?

Mikhail Prytkov: It depends on the business model and user perception. The business model dictates your payback cycle. Do you want to return more and quicker, or are you willing to lay up for a long time. That’s where you have to do the math as well, because there can be situations where a product with a one-year subscription has a very good renewal for the next year and beyond. And then you form a huge tail that lives for many, many years and fades very slowly. It gives you a huge LTV, but it takes a long time to come back. Next, there can be monthly subscriptions. But the shorter the subscription, the faster it will fade logically. The longer it is, the longer it takes.

The math here just counts, how in terms of ROI it should work, how in terms of strategy it should work. Whether you need a quick payback to buy the next user or whether you’re willing to wait and have mechanisms and some capital for the company to continue to exist at that point. A lot of different factors.

So if you look at it in the abstract, just looking at how other apps are doing, it’s not always obvious why that’s what they’re doing. There can be a lot of factors there. So the ideal way is to try what the strongest competitors are doing, to learn faster, to try to transfer the best practices to yourself. But then to think on my own about how I can improve it, so it fits my product and my business model better.

The negative effect of experimentation and increasing complexity

Vitaly Davydov: Speaking of more experiments. Any experiment is likely to have a negative effect. Are you doing something special to reduce this effect? Do you implement bandit or Bayesian tests instead of the usual A/B tests, or don’t you do them? Or do you just run it all on volumes… or do you quickly turn it off?

Mikhail Prytkov: We do not do it yet. That’s a minus. It has to be done. With A/B tests, of course, it’s difficult, especially in products with different seasonality within a week, with different traffic, because you have to wait. Sometimes you have to wait for quite a long time, i.e. we have a historically very clear trend. We used to have 5-6 out of 10 hypotheses we made that were positive. We were very good at guessing what needed to be done, and it worked. Now if it’s 1-2 out of 10, that’s lucky. That’s a straight up very good result. The difficulty is increasing. The elements are getting harder and harder to do effectively. So any ways to reduce the negative effect in negative experiments, that’s very important. We haven’t gotten there yet. Just doing a tool at our place to do an experiment.

Nikita Maidanov: Why is the complexity growing? Have you picked all the low-hanging apples or is the market just changing?

Mikhail Prytkov: Yes, all the low-hanging apples are quickly picked, it gets harder next. Not only is the market evolving, you don’t exist separately. What didn’t work for you a year ago may already be working this year. Your competitors work at the same time. They’re changing things. If they’re doing something fundamentally better, they’re changing the way users behave. So users begin to get used to another expression; the perception of your expression is already changing for them. There are not only competitors, but also established practices from big companies in design, expression, UX, and so on. That is, in everything.

Users get used to it. They want to use the best of what’s possible in a logical way. So the complexity is constantly increasing. In fact, you can’t stop. You have to keep doing experiments to be effective in this market. Otherwise, as the cost of procurement, the quality of projects in the mobile ecosystem grows at the same time, at the same time your competitors are trying to do something to make it work better for them. Accordingly, you just have to run faster than everyone else, do faster expe